A literature review of major life goals

Major Life Goals: An Essential and Complementary Construct to Traits

Abstract: This paper critically reviews the scientific literature on major life goals, the assessment for which was first developed by Richards (1966) and then revised by Roberts and Robins (2000). It begins with the story of how Roberts and Robins developed a taxonomy of life goals. Next, the findings of various studies on the stability of major life goals, the associations between major life goals and traits, and how these associations may vary across the life span are presented. These findings suggest that while major life goals and traits have strong associations, major life goals cannot be subsumed by traits entirely and instead are a complementary construct. Conceiving traits and goals in this way is in line with Neo-socioanalytic Theory (NST) rather than the Five-Factor Theory of personality (FFT). Many of these findings also support Baltes’ Socialization, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC) model of development (1997). The paper ends with a discussion of the conceptual relation between traits and goals and the importance of major life goals in the overall conception of personality as well as with a discussion of future directions for research.

Introduction

What do you want most out of life? Over the past several decades, personality psychologists have made considerable advancements pertinent to assessing individuals’ answers to this question, including developing a way to assess this normatively. In constructing a normative assessment, Richard Robins and Brent Roberts developed the concept of “major life goals,” which they define as “a person’s aspirations to shape their life context and establish general life structures such as having a career, a family, a certain kind of lifestyle, and so on…major life goals have a longer timeline and influence an individual’s life throughout years and decades rather than days and weeks” (2004, p. 1285). Since then, many studies have been conducted concerning major life goals with many of them providing evidence for the notion that major life goals are separate from but related to traits. Following the assumption of major life goals being a separate construct from traits and in light of other literature on broad frameworks of personality, major life goals should be recognized as essential to understanding an individual. The review of the existing literature on major life goals begins with Roberts and Robins developing their taxonomy of major life goals.

Part 1: Major life goal stability and associations with traits – Major life goals are different from but complementary to traits.

Establishing a Taxonomy of Life Goals

In 2000, Roberts and Robins wanted to attempt to answer the question: Do personality traits predict the goals a person chooses to pursue in life? However, a divide in the field made it difficult to answer such a question. They write, “Over the past few decades, two distinct lines of research—one focused on who people are (dispositions) and the other on what people desire to become (motives or goals)—have traveled separate paths” (2000, p. 1284).

In the dispositional line of research and the field as a whole, the development of the Five-Factor Model was a milestone moment. The now omnipresent taxonomy provides a way to “organize and categorize the myriad traits studied by personality psychologists into five broad content categories”. Furthermore, the Big Five are “conceptualized at the broadest level that retains descriptive utility,” and have been found to generalize across many different cultures and predict a wide range of outcomes (2000, p. 1284). However, at this time, there was no taxonomy serving the same function in the motive domain.

The lack of taxonomy for life goals presented two major problems when trying to conduct a study about the relation between dispositions and motives/goals. The first problem was that midlevel units and traits are conceptualized at different levels of breadth. Second, the motive/goal line of research had been focusing on ipsative assessment whereas traits are assessed normatively.

Therefore, Roberts and Robins developed a taxonomy that would allow them to examine the relation between traits and goals. In order to do this, they examined the relationship between Allport’s “major goals” (1961) which are conceptualized at a broad level similar to the dimensions of the FFM and traits. Then, they gathered a group of participants to rate the importance of the same set of goals. Finally, they used both conceptual and empirical procedures to organize life goals into thematic content clusters, resulting in a preliminary taxonomy of life goals, and allowing them to relate the goal clusters to personality trait differences and address whether individual differences in personality traits predict the major life goals a person chooses to pursue. The empirical procedures included reviewing seven taxonomies of values, which lie one level above life goals in the motivational hierarchy. As a result of their review, they identified 10 relatively conceptually independent value domains: theoretical, economic, aesthetic, social, political, religious/spiritual, physical well-being, relationship, hedonistic, and personal growth.

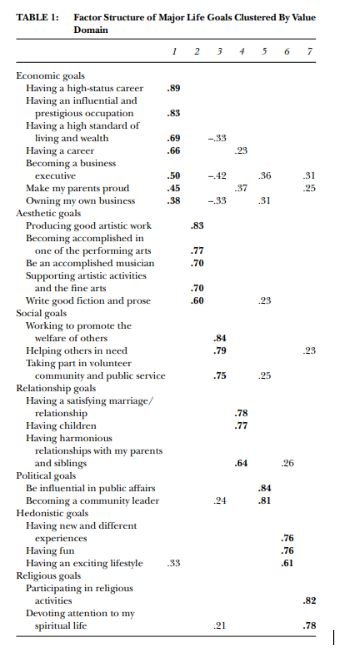

After identifying these domains, they searched the literature for an existing life goal-measuring instrument. The only comprehensive one they found that assessed normatively rather than ideographically was the one developed by Richards (1966). As a first step in their study, they conceptually classified the major life goals identified by Richards (in addition to some additional goals they generated concerning contemporary issues) into the 10 value domains derived from their review of the literature. They then conducted internal consistency assessments and factor analyses; they eliminated three of the goal clusters due to low alpha reliabilities. Finally, they had a taxonomy (see Appendix: Table 1) they could use to answer their question about the personality correlates of major life goals.

Answering the question: Do traits predict major life goals?

Roberts and Robins administered their newly developed measure and the NEO-Five Factor inventory on 672 undergraduate students and found many significant correlations between Big Five traits and major life goals (2000). Namely, they received confirmation for their hypothesis that the Big Five traits of Extraversion (β = .28) and Conscientiousness (β = .15) would be positively associated with economic goals. Interestingly, they also found that Agreeableness (β = –.19) and Openness to Experience (β = –.27) were negatively associated with economic goals. Therefore, economic goals were related to a profile of traits rather than one or two traits.

For political goals, they found that they were positively associated with Extraversion (β = .30) and negatively associated with Agreeableness (β = –.12). Social goals were positively related to Agreeableness (β = .27), Neuroticism (β = .16), and Openness (β = .17). Also consistent with their hypotheses, individuals high in Agreeableness tended to have higher relationship goals (β = .13). In addition, Extraversion (β = .26) predicted relationship goals. However, this pattern was not consistent across the individual goals comprising the domain. The desire to have a satisfying marriage or relationship was not predicted by any of the Big Five dimensions, which was most likely the result of the extremely skewed distribution and lack of variability in ratings of this goal. Openness to Experience was strongly related to aesthetic goals (β = .40). Hedonistic goals showed a complex set of associations with the Big Five. People who were more Extraverted (β = .39), more Open to Experience (β = .12), and less Agreeable (β = –.13) wanted to pursue more hedonistic activities. Religious goals showed little relation to the Big Five.

Implications of their Findings

These findings clearly show that traits do predict major life goals and support the notion that goals and traits are related; however, because the magnitude of the associations was modest, Roberts and Robins conclude that life goals are not subsumed by personality traits or vice versa. Rather, they believe they should be seen as “complementary units of analysis” (2000, p. 1293).

Although perhaps seemingly uncontroversial, this conclusion is actually related to another big divide in the field: among theories of personality, there are two prominent theories that differ in their assumptions about the relationship between traits and goals. According to Neo-socioanalytic Theory (NST), “goals and traits are related but discrete units of personality at the same level of analysis that independently contribute to life outcomes” (qtd. in Bleidorn et al., 2010). In contrast, according to the Five-Factor Theory of personality (McCrae & Costa, 1999), goals are causal outcomes of traits. That is, goals are indirect or direct expressions of personality traits, and goals can be completely subsumed by traits.

Luckily, the development of a taxonomy of major life goals allowed this idea to be further studied, allowing one to develop a clearer picture of whether goals can be subsumed by traits. In fact, the development of a taxonomy of major life goals sparked further research on the stability of major life goals at different points in the lifespan and over the course of different time spans. Many of these studies confirm the results found in this landmark study and further support the NST and the idea that traits and life goals are separate but related constructs.

The relation between traits and major life goals under different circumstances – during emerging adulthood

Four years later, Roberts et al. conducted such a study examining major life goals in a longitudinal study (2004). In particular, they chose to examine how continuity and change in major life goals compare to that of traits during the time period of “emerging” adulthood. They define major adulthood as the time in life when individuals make major decisions concerning the shape and content of their life course. In line with Baltes’ selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC) model of development, which says that this stage of life entails “narrowing down present options, based on current internal and external resources, and developing a personal hierarchy of goals,” Roberts et al. hypothesized that people would “progressively commit to fewer and fewer goals as they winnow down the options to those that best reflect their interests and abilities” (Baltes, 1997; Roberts et. al, 2004).

The participants consisted of 298 college-aged students. They rated the importance of their life goals 6 times over 4 years and completed a measure of the Big Five personality traits at the beginning and end of college.

In conducting a longitudinal study, they were able to assess whether changes in goal importance were related to changes in personality traits. They found that changes in goal importance were related to a wide range of changes in personality traits: changes in Economic goals were positively associated with changes in Extraversion (r = .15) and Conscientiousness (r = .19). Changes in Aesthetic goals were positively related to changes in Openness to Experience (r = .27), as well as to changes in Extraversion (r = .21). Changes in Social goals were positively linked to changes in the trait of Extraversion (r = .24) and Agreeableness (r = .15). Changes in Relationship goals showed a significant positive association with changes in Extraversion (r = .28), Agreeableness (r = .26), and Conscientiousness (r = .24). Similarly, changes in Political goals showed a significant positive association with changes in Extraversion (r = .40) and Conscientiousness (r = .21). Changes in Hedonistic goals were positively related to changes in Extraversion (r = .38) and Openness to Experience (r = .18). Finally, changes in the importance of Religious goals were unrelated to changes in personality. These findings of changes in goal importance being related to changes in personality traits support the idea that goals and traits are related.

In terms of stability, they found that similar to personality traits, life goals were highly rank-order stable. Correlations year-to-year ranged from .64 to .89 while 4-year rank-order consistency ranged from .44 to .71. However, unlike personality traits over the same time period from the same sample (the pattern for which will be elaborated on later), the mean importance of most life goals decreased over time. This is consistent with the SOC model of development.

These two findings in conjunction have interesting implications for the relationship between traits and major life goals. While the trait-like level of consistency supports the notion that goals are actually personality traits (in line with Costa and McCrae’s Five-Factor Model), the mean-level change in major life goals contradicts this idea because they do not follow the same developmental trajectory. Therefore, this appears to be further confirmation of the NST and the idea that while traits and life goals are related, neither traits nor life goals can be conceived as subsuming the other.

At the end of their paper, Roberts et al. suggest future directions for research writing, “Studying individuals experiencing major life transitions will allow researchers to test whether life goals stay as stable as personality traits when the context of the individual’s life is more fluid and unpredictable.”

The Relation Between Traits and Major Life Goals Under Different Circumstances: During a Transitional Period

In 2009, Ludtke et al. conducted a study doing just that, examining the continuity and change in the Big Five personality traits and the importance of life goals in 2,141 students in 2 years during the transition from school to college or employment. Ludtke et al. found that even during a period of transition, both personality traits and major life goals were highly rank-order consistent although the rank-order stability of life goal importance was a bit lower; the average two-year test-retest correlation was .53 in comparison to .69 for traits. This finding was of a similar magnitude as the one in Roberts et al. (average r =.56). Ludtke et al. also had similar findings about the trajectory of traits over time in comparison to the trajectory of life goal importance. While scores on the traits of Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness increased over time, and Neuroticism decreased (in line with the maturity principle), the importance of all major life goals with the exception of health decreased (Ludtke et al, 2009).

The Relation Between Traits and Major Life Goals Under Different Circumstances: Over a Longer Time Interval

In 2021, Atherton et al. conducted a study similar to these of Ludtke et al. and Roberts et al., but this time over a much longer time period of 20 years in comparison to two years and four years respectively. They examined the stability and change in personality traits and major life goals from college (age 18) to midlife (age 40) in 251 participants and even over this much longer time period, rank-order consistency in traits and life goals was moderate to high. The rank-order consistency of the Big Five over this 20-year time period ranged from a low of .46 for Neuroticism to a high of .81 for Openness to Experience. Life goals were also moderately stable across the 20-year period ranging from a low of .44 for hedonistic goals to a high of .58 for family/relationship goals. Furthermore, consistent with the findings of the previous studies, Atherton et al. also found differential patterns of development between traits and life goals, with mean-level increases in traits over this time period and mean-level decreases in the importance of life goals (2021).

The Relation Between Traits and Major Life Goals Under Different Circumstances: During the Transition to Parenthood

Additionally, in 2021, Wehner et al. conducted another similar study but this time examining the stability and change in personality traits and major life goals at a time where presumably some major life goals have already been achieved: during the transition to parenthood. Again, they found high-rank order consistency in life goals albeit during a probable time of immense change. They also found high ipsative stability. That is, even on an individual level, life goals tended to remain consistent in importance during the transition to parenthood. Interestingly, however, they did find several selection effects suggesting that women without children tended to endorse agentic life goals (They categorize Roberts and Robins’ seven domains in two broad domains: agency and communication. Agency goals encompass strivings related to power, variation, and achievement.) more than mothers did (Wehner et al, 2021). In general, though, these findings support the notion that life goals are quite stable even in times of change.

Collective Implications of Findings

Therefore, the findings of Roberts et al., Ludtke et al., Atherton et al., and Wehner et al. all offer strong support for the idea that major life goals are related but separate from traits. The findings from these four papers show that goals and traits are related because of the repeated associations between specific traits and goals and because both traits and goals were found to be highly rank-order consistent even in times of transition and across long time spans (although major life goals are slightly less so according to Ludtke et al.). On the other hand, the findings from these four papers show that traits and goals are separate constructs as they provide further evidence that traits and life goals do not follow the same developmental pattern with traits following the maturity principle (Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness increasing and Neuroticism decreasing) and major life goals largely decreasing in importance (again in line with the SOC model of development). All in all, these findings provide evidence that major life goals are related to but separate from traits at all points in life and over large time intervals. This provides further support for the NST.

While the findings of the aforementioned papers were largely in line with one another, the findings of Ludtke et al. and Atherton et al. contradicted one another when it came to looking at whether there were effects of prior personality traits on subsequent life goal importance or if there were effects of prior life goal importance on subsequent personality traits. Using reciprocal effects models, Ludtke et al. found that there were effects of prior personality traits on subsequent life goal importance. The most pronounced associations for each trait were the positive relations between Extraversion and Hedonism (r = .34), Agreeableness and Community (r = .41), Conscientiousness and Health (r = .22), Neuroticism and Image (r = .17), and Openness and Personal Growth (r = .54). However, they found almost no effects of prior life goal importance on subsequent personality traits (Ludtke, 2009).

Contrastingly, Atherton et al. did find some effects of prior life goal importance on subsequent personality traits. For example, they found that individuals who had higher levels of Hedonistic goals at the beginning of college showed greater decreases in Extraversion (r = −.34) and that individuals who had more Religious goals at the beginning of college showed greater increases in Openness to Experience over time (r = .26). Considering the Atherton et al. study examined a much longer time period (20 years in comparison to 2 years), their findings are more convincing. Assuming that their findings are accurate, this provides further support in favor of NST as it is difficult to reconcile traits subsuming major life goals if life goals predict future trait development. As for the mechanisms behind such change, Atherton et al. theorize that people formulate goals consistent with their personality traits, and investing in goal-relevant contexts is associated with trait change.

Major Life Goals Through Other Lenses: Relations to Vocational Interests

While a majority of studies concerning major life goals and their relationship to traits have explored consistency and change over time, a number of researchers have chosen to explore major life goals through a slightly different lens, including involving the taxonomy of vocational interests. For instance, in 2020, Stoll et al., in addition to confirming the finding that major life goals are associated with Big Five, sought to find out whether major life goals are associated with vocational interests and specifically, if vocational interests add incremental validity in explaining major life goals. That is, do vocational interests explain additional variance above and beyond traits?

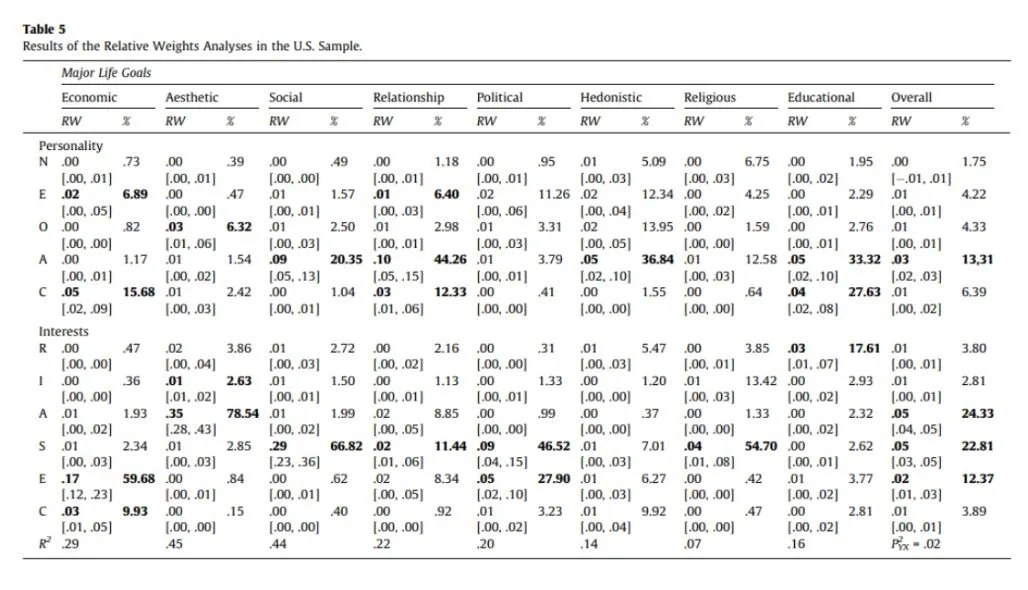

In their studies, Stoll et al. confirmed that Big Five personality traits alone explained between 2% and 22% of the individual differences in major life goals. Many of these findings confirmed the findings of Roberts et al. For example, Stoll et al. also found associations between Aesthetic goals and Openness, Relationship goals, and Agreeableness in addition to Extraversion, Hedonistic goals, and Extraversion, etc. (A full list of findings can be found in the Appendix: Table 5). In comparison, vocational interests alone explained between 5% and 43% of the individual differences in major life goals. Together, personality traits and vocational interests explained between 7% and 45% of the variability in major life goals (Stoll, et al., 2020).

The findings of this study in particular are interesting in considering the relationship between traits and major life goals, as this study strongly suggests that major life goals are even more strongly related to something besides traits: vocational interests. Assuming this finding is accurate, this seems to further suggest that traits are not the ultimate cause of major life goals and provides further evidence for the idea that while related, traits and goals are separate, complementary constructs.

Major Life Goals Through Other Lenses: Focusing on the Relations Between Major Life Goals and the Trait of Openness

Douglas et al. (2016) took an even more unique approach to examining the relationship between traits and life goals, choosing to focus only on the Big Five trait of openness. In their studies, they aimed to examine the discriminant validity of Openness and Intellect in their relationship to values, interests, and major life goals, administering an online survey assessing Big Five Aspect Scales, Schwartz's Values, Holland's Interests, and Major Life Goals. In all three studies, they found that openness was a significant and positive predictor of aesthetic life goals, in addition to artistic interests. In one of their studies, they also found aesthetic life goals to be also positively associated with Social and Hedonistic Major Life Goals, and negatively with Economic Major Life Goals, however, none of these regressions reached the effect size threshold of d = 0.15, indicating a lack practical effect of Openness on any of these goals. Considering that they found an association between openness and aesthetic life goals in all three of their studies, even when using a relatively high threshold of practical effects, they assert that this association is likely to be a robust finding (Douglas et al., 2016). In the bigger picture of the relationship between traits and major life goals, this study offers support for the relatedness of the two constructs, particularly between aesthetic life goals and openness. This finding was found in nearly all of the aforementioned studies as well, pointing to even stronger support for their relatedness.

Major life goals through other lenses: The Nature and Nurture of the Interplay Between Personality Traits and Major Life Goals

In 2010, Bleidorn et al. took a completely different approach to exploring the relationship between traits and major life goals seeking to examine the genetic and environmental sources of the interplay between the Big Five and major life goals concurrently and across time. Traits and goals were assessed twice across a 5-year period in a sample of 217 identical and 112 fraternal twin pairs. Since the FFT posits that traits are the ultimate cause of goals, findings of higher heritability for traits (indicating that genetic effects on goals can be accounted for by genetic effects on traits) and the lack of genetically and environmentally mediated effects of goals on traits would support the FFT. On the other hand, since the NST posits that traits and goals represent two discrete but related units of personality at the same hierarchal level, findings of minimal difference in heritability for goals in comparison to traits and the presence of genetically and environmentally mediated effects of goals on traits would support the NST.

They found that in comparison to Big Five traits, for which it is well-established 40% to 60% of the variance in self-reports of broad personality traits is genetic in origin, the amount of variance in self-reported major life goals was notably lower. The relatively lower heritabilities of major life goals indicate that goals are more susceptible to external influences of the environment than personality traits. This finding is more in line with the FFT; however, in their longitudinal multivariate analyses, they found significant (although small) genetically and environmentally mediated effects of prior life goals on subsequent personality traits, supporting the NST and the assumption that goals are more than mere expressions of traits. Bleidorn et al. write “Instead of a causal precedence of traits over major life goals, our findings speak for a reciprocal interplay between traits and goals over time. That is, people do not only adapt their life goals to their preexisting personality traits but also adjust their traits in the service of pursuing their major strivings in life.”

Part 2: Where major life goals fall in the conception of personality and their importance - Major life goals are essential in the conception of personality.

A Framework that integrates the FFT and NST

While it is appealing to explain away the finding that contradicts whichever side you find yourself more privy to (FFT or NST), Bleidorn et al. present McAdams and Pals’ (2006) conceptual framework as a way to reconcile these seemingly conflicting findings. In their framework, McAdams and Pals integrate aspects from both the FFT and NST, landing somewhere in the middle. (Note that they often refer to goals in conjunction with other constructs collectively as characteristic adaptations.) In line with the FFT, their framework considers characteristic adaptations, such as goals, to be more malleable than traits and for traits to influence characteristic adaptations. On the other hand, in line with the NST, characteristic adaptations are not always conceptualized as being entirely determined by interactions between traits and the environment. Instead, they believe some characteristic adaptations, like major life goals, can have their own developmental trajectory, function, and importance (McAdams & Pals, 2006).

McAdams’ Three Levels and The Importance of Major Life Goals in the Conception of Personality

These ideas are of course heavily in line with some of McAdams’ earlier ideas, which in some ways support the notion that major life goals are essential to understanding a person. McAdams is known for conceptualizing personality using three levels: traits, “personal concerns,” and life narratives. We are of course familiar with the first level of traits; however, McAdams is adamant that traits are not sufficient for understanding an individual. In particular, he cites the following limitations of traits: “Traits typically do not provide enough specific information to make for the effective prediction of behavior in particular situations and for the kind of rich description of human lives that clinicians and laypersons expect” (McAdams, 1994, p. 302) He further asserts that traits don’t account for the contextual and conditional nature of human experience writing: “To know a person well one may also seek to obtain, for example, information concerning what the person wants, how the person goes about trying to get what he or she wants, what the person is concerned with, what the person is “into,” what his or her plans for the future are, how the person feels about his or her children and wife or husband and boss, the person’s plans, goals, strivings, projects, tactics, strategies, defenses, and so on” (1994, p. 304). He gives this level the label of “personal concerns.” This level certainly encompasses the concept of major life goals and in arguing for the necessity for personal concerns, he explicates precisely why motivational constructs are essential for understanding a person. Because major life goals were designed to encompass motivational constructs at such a broad level, one can reasonably assume that McAdams would support the idea that major life goals are an essential aspect of personality.

Part 3: Future directions

In light of the importance of major life goals, although many studies have already been conducted on the topic, there are still many possible interesting directions for future research. In particular, the following ideas would be fascinating to study further: examining major life goals in an older population, exploring other ways of assessing goals rather than just focusing on their importance, and examining the relationship between major life goals and other constructs further.

In terms of examining major life goals in an older population, the oldest participants in many of these studies were only in midlife. It seems more plausible that major life goals could change considerably after midlife and therefore it would be interesting to see if major life goals do indeed change after midlife and in what way. Additionally, because the second half of life often involves retirement, it would be interesting to see how that affects major life goals as some directly involve the notion of a career. Furthermore, while we observe a general decrease in the importance of major life goals in all domains during and up to midlife (in line with the SOC model of development) because some goals may be achieved by midlife, perhaps life goal importance will be more likely to switch domains in the second half of life. In general, studies examining older populations could illuminate the extent to which goal achievement predicts the rank-order stability of major life goals across the lifespan.

As for assessing goals in other ways besides their importance, according to Roberts et al. (2004), asking people to evaluate their goals in a variety of different ways is a hallmark of the idiographic approach to goal assessment. For instance, one could evaluate participants’ goals with regard to how much they are working on accomplishing the goal, how happy they are with their progress, and how much conflict they experience between goals. It is possible that assessing goals in other ways would reveal new patterns with regard to the relation between traits and goals and therefore, studies examining these alternative aspects of goals would be incredibly informative.

Lastly, like Stoll’s study (2020) examining the relationship between major life goals and vocational interests, other studies could also investigate relationships between major life goals and other constructs and their relationships over time. For instance, Stoll et al. (2020) suggest that longitudinal studies could be conducted to test for reciprocal relations between the three groups of constructs (vocational interests, traits, and major life goals) and to investigate how they develop together across time. It would also be interesting to investigate the relation between other motivational constructs like values, smaller-scale goals, ideal and ought selves, and major life goals, especially considering their hierarchical relationships. A study examining the relationship between major life goals and Schwartz’s Theory of Basic Human Values (Schwartz, 2012) would be particularly interesting because of its circumplex nature.

Conclusion

The taxonomy of major life goals offers a way to measure what people want out of life in a similar way to how the Big Five personality traits measure what a person is like. In this paper, we discussed at length how traits are complementary yet separate from traits, and while traits offer a great deal of insight into what a person is like, without knowing what they want at the broadest level, it is hard to say you really know them, so when someone asks, “What do you want most out of life?” answering with your major life goals may be a good place to start.

References

Allport, G. W., Vernon, P. E., & Lindzey, G. (1960). Study of values.

Atherton, O. E., Grijalva, E., Roberts, B. W., & Robins, R. W. (2021). Stability and change in personality traits and major life goals from college to midlife. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(5), 841-858.

Baltes, P. B. (1997). On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: Selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of developmental theory. American psychologist, 52(4), 366.

Bleidorn, W., Kandler, C., Hülsheger, U. R., Riemann, R., Angleitner, A., & Spinath, F. M. (2010). Nature and nurture of the interplay between personality traits and major life goals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 99(2), 366.

Douglas, H. E., Bore, M., & Munro, D. (2016). Openness and intellect: An analysis of the motivational constructs underlying two aspects of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 242-253.

Lüdtke, O., Trautwein, U., & Husemann, N. (2009). Goal and personality trait development in a transitional period: Assessing change and stability in personality development. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(4), 428-441.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1999). A five-factor theory of personality. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 139 –153). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

McAdams, D. P. (1994). Can personality change? Levels of stability and growth in personality across the life span.

McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2006). A new Big Five: fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. American psychologist, 61(3), 204.

Richards Jr, J. M. (1966). Life goals of American college freshmen. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 13(1), 12.

Roberts, B. W., & Robins, R. W. (2000). Broad dispositions, broad aspirations: The intersection of personality traits and major life goals. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 26(10), 1284-1296.

Roberts, B. W., O'Donnell, M., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Goal and personality trait development in emerging adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(4), 541.

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 2307-0919.

Stoll, G., Einarsdóttir, S., Song, Q. C., Ondish, P., Sun, J. J., & Rounds, J. (2020). The roles of personality traits and vocational interests in explaining what people want out of life. Journal of Research in Personality, 86, 103939.

Wehner, C., Scheppingen, M. A. V., & Bleidorn, W. (2022). Stability and change in major life goals during the transition to parenthood. European Journal of Personality, 36(1), 61-71.

Appendix